Global

Financial Markets

by Ian H. Giddy

|

Understanding and Using

Hybrid

Financial Instruments |

Contents: Constructing

the Edifice--Economics of Financial Innovation--Competition and the Product

Cycle in Financial Innovations--Sources of Innovations--Transactions and

Monitoring Costs--Regulation--Taxes--Constraints--Market Segmentation--Box:

Asset-Backed Securities in Turkey--Understanding New Instruments: The Building

Block Approach--Hedging and Managing New Instruments: The Functional Method--Box:

Application: Valuation of an Oil-Linked Bond--Hybrids in Corporate Financing--Box:

Structured Financing: A Sequence of Steps--Global Financial Markets in

the Next Decade--Summary1

Constructing

the Edifice

The international financial

market has altered dramatically in the last decade, and is likely to continue

to do so. As we have seen in previous chapters the Eurobond market has

proved fertile ground for the introduction of many experimental techniques,

while the recent opening up of domestic capital markets may augur a burgeoning

of instruments designed to meet the requirements of investors and issuers

in the home markets. Today's potential investor or issuer is confronted

with dual currency bonds, reverse dual currency bonds, with swaps and options

and swaptions and captions, and with "bunny bonds" and "bull and bear"

bonds and TIGRS and Lyons. Flip-flops and retractables and perpetuals and

Heaven-and-Hell bonds. Bonds linked to the Nikkei index or German Bund

futures contracts or the price of oil. What's it all about, one has to

wonder. Who buys these things? Who issues them, and why?

This chapter introduces a

practical approach to the analysis and construction of innovative instruments

in international finance. Many instruments of the international capital

market, new or old, can be broken down into simpler securities. These elementary

securities include zero-coupon bonds, pure equity, spot and forward contracts

and options. Later in this chapter, for example, we will analyze the breakdown

of a dual currency bond into a conventional coupon-bearing bond and a long-dated

forward exchange contract. Combining or modifying basic contracts is what

gives us many of the innovations we see today, and if we understand the

pricing of bonds, forward contracts and the like, we can in many

cases estimate the price of complex-sounding instruments. When one encounters

a new technique, one seeks to understand its component elements.

We call this the

building block approach. We'll see numerous examples

in the pages that follow.

The building block method

also enables us to go a step further: to understand the role of such securities

in a portfolio of assets or liabilities. An extension of the building block

approach is one that teaches us the behavior of innovative securities,

alone or in combination. Simply stated, this functional method regards

every such instrument or contract as bearing a price or value, which

in turn bears a unique relationship to some set of variables such as interest

rates or currency values. The more one can break the instrument down into

its component parts or building blocks, the easier it is to specify how

the instrument's value will change as the independent variables change.

Once we know how the instrument

is constructed and hence how its value behaves, we can readily compare

it against existing instruments which, alone or in combination, produce

the same behavior. For example, some instruments' value varies with market

interest rates, so that they are bond-like; others are affected by the

condition of the issuing company, so that they are more equity-like. Many

instruments combine elements of both. Each should be priced in accordance

with the price of comparable instruments; if they are not, there may be

a mispricing. The functional approach can be of great practical value to

investors and issuers who wish to better understand the risks of instruments

offered to them by banks. The approach can also be used to identify arbitrage

opportunities between instruments, and to hedge one instrument with another.

We begin by seeking to explain

why it is that new instruments are introduced, and which are likely to

succeed.

Back to

top

Economics

of Financial Innovation

No financial innovation can

be regarded as useful, nor will it survive, unless it creates benefits

to at least one of the parties involved in the contract. These benefits

could involve lower costs of capital for the issuer or higher returns for

the investor. The benefit could be lower taxes paid. Or a reduction in

risk, such as foreign exchange exposure of a corporation or government.

More generally, the contribution of any financial innovation lies in the

extent to which it helps complete the set of financial contracts available

for financing or investing, positioning or hedging. They are introduced

in response to some market imperfection.

Example

In the early 1980s certain

German banks introduced investment instruments whose return was equal to

the change in the German stock market index, the DAX, including reinvested

dividends. This enabled German individual investors to overcome the absence

of an equity index futures contract in Germany and to avoid the high fees

charged by investment trusts.

|

But even if both the investor

and the issuer are better off, there will only be a net gain if these benefits

more than offset the costs of creating the innovation. These costs include

research and development, marketing and distribution costs. Moreover, the

firm providing the innovation must be able to capture or appropriate some

of the benefits generated.

One fundamental factor inhibiting

investors' demand for new instruments is that something new and different

tends to be inherently illiquid. If an instrument is one of a kind,

traders cannot easily put it into a category that allows it to be traded

at a predictable price and in a positioning book along with similar instruments.

And to the extent that the new instrument is difficult to understand,

the costs of overcoming information barriers may inhibit secondary market

development.

Some innovations may actually

destroy

value, because they are misunderstood by one party to the contract.

The instrument does not behave in the way it is described as behaving.

Or one aspect of the risk of the instrument (such as the credit risk of

swaps) is not fully appreciated by one party. The excessive investment

by U.S. savings and loan institutions in high-yield "junk" bonds in the

1980s can be seen in this light. These securities were described as bonds

with disproportionately high yields. Yet a functional analysis of their

behavior reveals that they were much more akin to equity than to bonds,

and so should have borne a return like the equity return of the issuing

company. Superficial analysis can lead to completely inappropriate investment

or financing.

In many instances the investor

or issuer may not be aware that he could have done the same thing cheaper

via another combination of instruments. This is not an indictment of the

banker promoting the instrument. In principle one can always find some

way in which the issuer (for example) could have done better had her investment

banker more fully informed her of all the alternatives. Bond salespeople

and corporate finance specialists do not have an obligation to fully inform

the client about all the alternatives (including competitors' products),

unless that information is explicitly paid for. There are many situations

in which the investor or issuer could in principle have found a cheaper

solution elsewhere, but faced transactions costs, regulations or high costs

of information-gathering that prevented ready access to the ostensibly

cheaper alternative.

One way to interpret this

is to describe financial product innovations as "experience goods." They

must be consumed before their qualities become evident.

For innovations to be produced

they must provide an above average return. Innovation of any kind involves

the production of an information-intensive intangible good whose value

is uncertain. While often costly to produce, new information can be used

by any number of people without additional cost: it is a common good. The

socially optimal price of a public good is zero. Indeed the ease of dissemination

of new information makes it likely that its price will quickly fall to

zero. However if this new information, once produced, bears a zero price,

there is little or no private incentive for the production of innovations.

There is no effective patent protection for financial instruments.

Yet a few firms seem to have

been leaders in the production of innovations. Because financial products

are experience goods, it may be that customers will tend to purchase new

instruments and services chiefly from firms that have a reputation for

initiating techniques of sound legality and predictable risk. Whenever

the true risks, returns or other attributes of the new instrument are difficult

to ascertain, there will be fixed information costs that serve as a barrier

to acceptance of that instrument. The imprimatur of a reputable firm can

allay investors' or issuers' fears. This is particularly true where the

issue must be done quickly to take advantage of a "window" in the market,

as the example of the first "collared sterling Euro floating rate note"

shows.

Hence, despite the absence

of legal proprietary rights, reputable banks and other financial institutions

will have a temporary monopolistic advantage that enables them to appropriate

returns from investment in the development of financial innovations. Other,

perhaps more inventive, firms and individuals will tend to be absorbed

by those who command a temporary monopoly.

Example

In the autumn of 1992 Britain

dropped out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, freeing its domestic

monetary policy from the constraints of a tie to the Deutschemark. On Tuesday,

January 26, 1993, the Bank of England lowered the base rate, Britain's

key short term rate, from 7% to 6%. On Thursday of that week Salomon

Brothers in London led the first issue of collared floating-rate notes

in sterling. The bond was a £100 million 10-year issue for the

Leeds Permanent Building Society.

The deal offered investors

LIBOR flat, with a minimum interest rate of 7 percent, 7/8 points higher

than the current six-month London interbank offered rate, and a maximum

of 11 percent. This is typical of the collared FRN structure, of which

over $8 billion had been done in dollar-denominated form at the time. Collared

FRNs incorporate a floor and a cap on the floating rate, with the floor

being above current money market rates to attract coupon-hungry

investors. The steep yield curve in the United States in the early 1990s

made it possible for issuers to sell caps and buy floors in the over-the-counter

derivatives market, and to use them to subsidize the cost of the issue

while offering the investor an above-market yield, at least initially.

Salomon Brothers had arranged

a number of deals of this kind in the dollar Eurobond market, and had done

preparatory work for a sterling version. It was not until the base rate

cut made the British yield curve steepen that it became viable, however,

and Salomon was quick to exploit the window. The opportunity to reduce

funding costs, and confidence that Salomon had the experience and credibility

to get it right, are factors that gave Leeds Permanent the confidence to

pioneer the structure in sterling. Similar collared FRNs were soon issued

by other UK building societies and banks.

|

Back

to top

Competition

and the Product Cycle in Financial Innovations

The advantage certain firms

have in new instruments is, before long, eroded as uncertainty is reduced

and clients can more confidently turn to lower-cost imitators. The high

initial returns are eroded by competition from other banks as well as by

the market forces that tend to eliminate those imperfections that gave

rise to the innovation in the first place. The product may become a "commodity."

For example, when interest rate caps were first introduced, corporate acceptance

was long and difficult and only a few firms with high credibility were

able to profit from them, and this only because the margins were substantial.

As familiarity and acceptance increased, the field was invaded by

many banks and securities houses with the ability to trade and broker these

interest rate options and prices of caps were driven down to a level resembling

that of the underlying options. At this point the low-cost producers assumed

a large market share.2

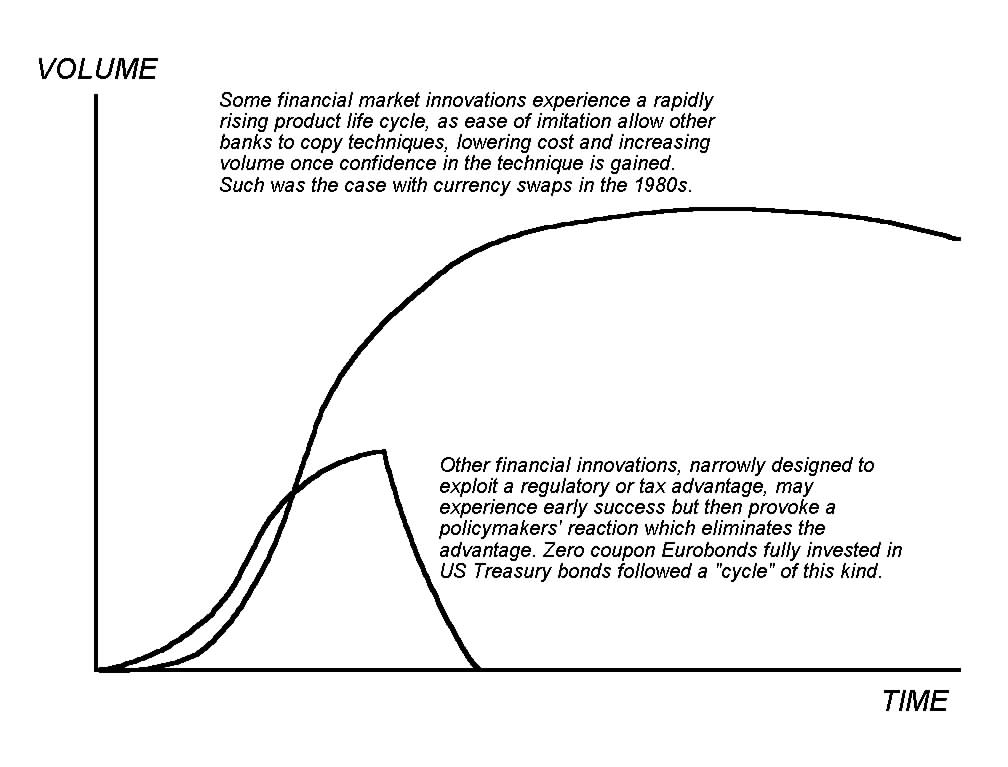

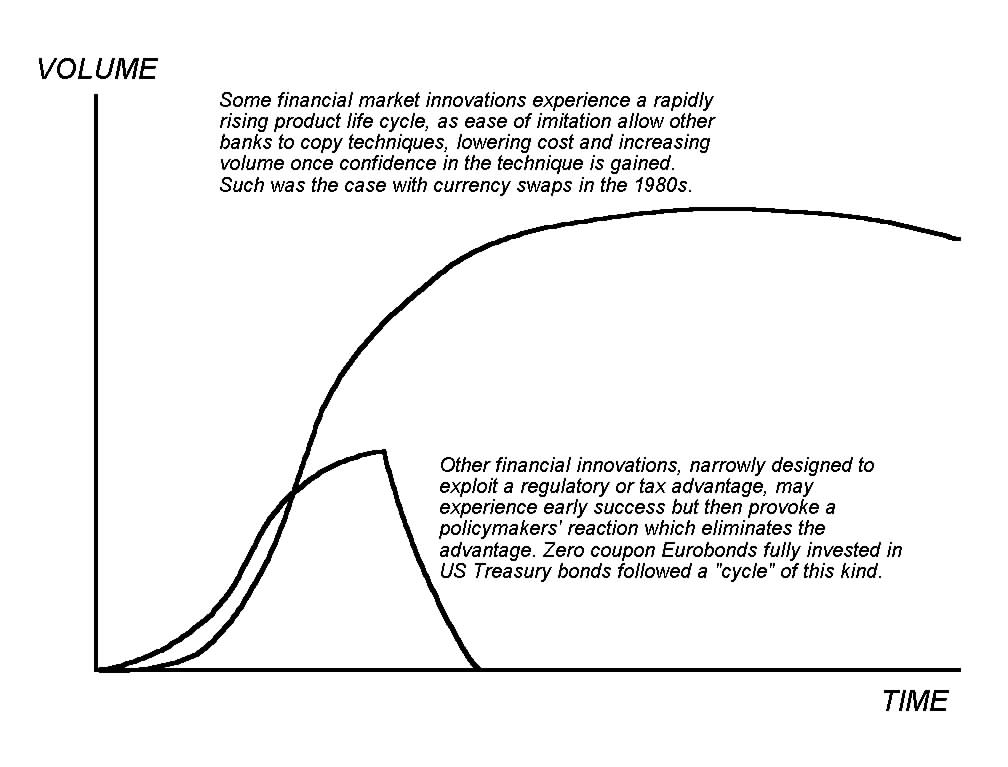

This

sequence can be illustrated by means of the "product life cycle" diagram

familiar to many readers. Financial innovations behave like other new products,

albeit with a faster dissemination rate. Some financial innovations, however,

set in motion a different process, one which leads to their demise. That

process is nor a market one but a political/regulatory process. Many innovations,

after all, are designed to circumvent regulations, restrictions and taxes.

The regulatory authorities, seeing that the technique has an erosive effect

on their jurisdiction, react by closing loopholes or by eliminating the

barrier that motivated the innovation in the first place.

This

sequence can be illustrated by means of the "product life cycle" diagram

familiar to many readers. Financial innovations behave like other new products,

albeit with a faster dissemination rate. Some financial innovations, however,

set in motion a different process, one which leads to their demise. That

process is nor a market one but a political/regulatory process. Many innovations,

after all, are designed to circumvent regulations, restrictions and taxes.

The regulatory authorities, seeing that the technique has an erosive effect

on their jurisdiction, react by closing loopholes or by eliminating the

barrier that motivated the innovation in the first place.

Back to

top

Sources

of Innovations

The majority of financial

innovations are just different ways of bundling or unbundling more basic

instruments such as bonds, equities and currencies. Of course there are

many, many different ways of rearranging the basic financial products.

So two puzzles arise. First, why do particular innovations seem to emerge

and thrive? And second, why do investors or issuers need the innovation

in the first place: what's to stop them from putting together the structure

from the basic instruments themselves, rather than paying investment bankers

to do so? The answer lies in imperfections--market imperfections that make

the

whole worth more than the sum of the parts, and which constrain investors

or issuers or both from constructing equivalent positions out of elemental

instruments. Many of these imperfections arise from barriers to international

arbitrage, from currency preferences, and from the different conditions

investors and issuers face in different countries.

The example of convertible

Eurobonds will serve to illustrate this concept.

Example

In 1992 a British company,

Carlton, issued a £64.25 million convertible, bearer form Eurobond.

The subordinated issue had a fifteen year life and paid a coupon of 7.5%,

at least 2% lower than comparable straight Eurobonds issued at the time.

The late 1980s and early

1990s saw a huge volume of Eurobonds with equity features issued by U.S.,

Japanese and European corporations. A convertible bond pays a lower-than-normal

coupon but gives the investor the right to exchange each bond for a certain

number of shares in the issuing company. Once the issuer's share price

rises by more than the conversion "premium" the investor has more to gain

from conversion than from holding the bond to maturity. As in the Carlton

case, the company often has a call option, giving it the ability to compel

the investor to choose between redemption and conversion when the shares

exceed the conversion price by a comfortable margin. This has the effect

of forcing conversion. The question: why would one choose to

buy this hybrid instrument rather than a bond alone, or an option on the

stock alone, or--if the investor wants the benefit of both--a combination

of the two? Three answers are possible :

First, one

might say that perhaps there is no domestic equity option market

available to the investor, possibly because regulations do not permit it,

giving rise to the need for an international proxy. This has been

true in Japan, which helps explain why so many Japanese companies have

issued Eurobonds with warrants.3

The latter, being separable, provide a better solution to the incomplete

markets argument than convertibles. And there are active equity option

markets in other countries, such as the United States and Britain.

A second explanation

lies in the freedom of certain offshore instruments from domestic taxes.

Eurobonds are issued in locations free of withholding taxes and in bearer

form, which helps preserve investor anonymity. But all shares are issued

by the parent company directly, and are listed and registered in the home

country. Registration means that the issuer, and therefore the fiscal authorities,

are told the share owner's identity. So individual investors seeking to

avoid paying taxes on their equity portfolios find that convertible Eurobonds

offer the "play" of equity without undue tax risk. When it comes time to

convert, the bonds are sold to equity investors in the country of the issuer

who are not concerned with the fact that the shares are registered.

Many convertible bonds are

also bought by institutional investors that do not have a tax avoidance

motivation. These buyers are getting around a regulatory or self-imposed

rule restricting equity investments. Some pension funds, for example, are

not permitted to buy equity. Convertible bonds give them participation

in the upside gain on the shares while guaranteeing interest and repayment

of the bonds should the shares fall. Sound conservative? The problem is

that the market price of a convertible bond rises and falls like

the shares when the embedded option is in the money or near the money.

So the institutional investor may be violating the spirit if not the letter

of the restriction.

|

At least five kinds of market

imperfection, alone or together, seem to make the whole worth more than

the sum of the parts in hybrid international securities. Thus we can identify

(1) innovation that results from transactions costs or costs of monitoring

performance (2) regulation-driven innovation, (3) tax-driven innovation,

(4) constraint-driven innovation, and (5) segmentation-driven innovation.

We will illustrate some of these by reproducing the "tombstone" announcements,

which serve no purpose except to proclaim the bankers' prowess: a sort

of investment banker's graffiti.

Transactions and monitoring

costs are the explanation for many instruments in today's capital market.

Most mutual funds offer individual and medium sized investors economies

of scale to overcome the erosive effect of brokerage, custody and other

costs associated with buying, holding and selling securities, costs which

can be particularly high for international investors. Ecu-denominated

bonds and other currency-cocktail bonds offer built-in currency diversification.

The costs of assessing and monitoring performance on contracts can also

deter many from employing simple techniques like forwards, debt and options.

Where monitoring costs are high, credit risk must be eliminated, usually

by means of one or both of two techniques: collateral and marking-to-market

with cash compensation. Thus the futures contract enables poor-credit companies

to hedge future currency, interest rate and commodity price movements without

monitoring costs.

For investors who wish to

take a position in a currency, equity or commodity, credit risk considerations

often preclude them from doing forwards or swaps directly. They can, however,

buy bonds whose interest or principal varies with the market price of interest--their

"counterparty," the issuer, has no credit risk, for instead of the investor

making a payment if he loses, the issuer simply reduces the interest or

principal to be paid to the investor. A callable bond falls into this category.

Regulation-driven innovations.

Laws and government regulations restrict national capital markets in many

ways. Banks, issuers, investors and other market players are prevented

from doing certain kinds of financing or entering into certain kinds of

contracts. For example banks are told that a certain proportion of their

liabilities must be in a form that qualifies as "capital" for regulatory

purposes, a requirement that stems from the international agreement known

as the "Basle Accord." Hence the financial papers are filled with announcements

of "convertible exchangeable floating rate preferred stock" and the like,

fashioned purely to meet the capital requirements. Issuers may not be permitted

to issue public bonds without intrusive disclosure. Insurance companies

may not be allowed to invest more than, say, 20% of their assets abroad

despite a paucity of domestic investment opportunities. These laws and

regulations may be well intentioned but may have unanticipated side effects

or become redundant as markets and institutions mature and economic conditions

change. Yet entrenched interests develop around certain rules making them

difficult to changes. Sometimes, as when interest rates or taxes reach

unusual levels, or when competition threatens, financial market participants

find it worthwhile to devise ways to overcome the restrictive effect of

outdated or misguided regulations.

For example, in the 1980s

foreign investment in Korean equities was severely restricted. One way

to get around this was for prominent Korean companies to issue Eurobonds

that were convertible into common stock. Since the bonds behaved like equity,

they served the international investor's purpose, to a degree.

February 1982

These bonds having already been sold this announcement appears as a matter

of record only

Japan Air Lines Company,

Ltd.

(incorporated with limited

liability under the laws of Japan)

U.S. $ Denominated 7f%

Yen-Linked Guaranteed Notes 1987

of a principal amount

equivalent to

Yen 8,600,000,000

Unconditionally and

irrevocably guaranteed by

Japan

Daiwa Securities Co. Ltd

Morgan Guaranty Ltd Bank of Tokyo Intl Ltd Banque

de Paris et des Pays-Bas Credit Suisse First Boston Ltd

Development Bank of Singapore IBJ International Ltd

Kuwait Investment Company (S.A.K.) Nikko Securities Co. (Europe)

Ltd Salomon Brothers Intl Swiss Bank Corporation

Intl Ltd S.G. Warburg & Co. Ltd

Algemene Bank Nederland

N.V. Amro intlBanco del Gottardo Bank of America Intl ltdBank of Tokyo

(Holland) N.V. Banque de l'Indochine et de Suez

Banque de Neuflize, Schlumberger, Mallet Banque Nationale de

Paris Barclays Bank Baring Brothers & co. Ltd

Caisse des Depots et Consignations Chase Manhattan Ltd

Chemical Bank Intl Group Citicorp Intl group Commerzbank

Aktiengesellschaft Continental illinois Ltd County

bank Ltd Credit Commercial de France Credit Industriel

et Commercial Credit Lyonnais Creditanstalt-Bankverein

Dai-Ichi Kangyo Intl Ltd DBS-Daiwa Securities Intl Ltd

DG Bank Deutsche Genossenschaftsbank Dillon, read Overseas

Corporation Fuji International Finance Ltd Goldman

Sachs Intl Corp. Hill, Samuel & CO. Ltd The

Hongkong Bank Group Industriel Bank Von Japan (Deutschland)

Aktiengesellschaft Kuwait Foreign Trading Contracting and Investment

Co. Kidder, Peabody Intl Ltd Kleinwort, Benson

Ltd Lloyds Bank Intl Ltd LTCB International Ltd

Manufacturers Hanover Ltd Merrill lynch Intl & Co.

Mitsubishi bank (Europe) S.A. Mitsui Finance Europe Ltd

Samuel Montague & Co. ltd Morgan Grenfell & Co. Ltd

Morgan Guaranty Pacific Ltd Morgan Stanley Intl

New Japan Securities Europe Ltd Nippon Credit Bank Intl (HK)

Ltd Nippon Kangyo Kakumaru (Europe) S.A. Nomura

Intl ltd Orion Royal Bank Ltd Sanwa Bank (Underwriters)

ltd J. Henry Schroder Wagg & Co. Ltd Societe

Generale Societe Generale de banque S.A.

Sumitomo Finance International Taiyo Kobe Bank (Luxembourg)

S.A. Tokai bank Nederland N.V. Union Bank of Switzerland

(Securities) Ltd Wako International (Europe) Ltd

Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale Wood Gundy Ltd

Yamaichi Intl (Europe) Ltd

|

Circumvention of regulation

is the source of many innovations that are not what they seem at first

glance. An example is the yen-linked Eurobond issued by Japan Air Lines

in the mid-1980s and illustrated in Figure 2. This deal was done when the

Japanese capital market was more protected than it is now. Foreign borrowers

were not allowed into the domestic bond market, and all domestic yen bonds

were subject to a withholding tax of 15%. Japanese firms were not permitted

to issue yen-denominated Eurobonds, although they were, with Ministry of

Finance approval, allowed to issue Eurobonds denominated in other currencies.

JAL wished to save money

by issuing a Eurobond, free of withholding tax, on which it would pay a

lower rate than one subject to the tax. But it wanted yen, not dollar financing.

The currency swap market did not yet exist. So JAL issued a dollar-denominated

Eurobond which repaid a dollar amount equivalent to ¥2.8 billion. In

effect, the principal redemption was yen-denominated. But the interest

was also yen linked, for as the tombstone suggests the coupon paid was

a fixed percentage, 7 7/8%, of the yen redemption amount. So for all intents

and purposes, it was a yen bond; but it satisfied the letter of the law

in Japan, and did so with the approval of officials at the Ministry of

Finance, who were in effect giving selected Japanese companies a back-door

feet-wetting in the Euroyen bond market. (The fact that the JAL deal was

officially sanctioned is evident from the name of the guarantor, and from

the veritable who's-who of international investment banking listed as underwriters.)

In due course the front door was opened, and later the withholding tax

removed. This illustrates the reality that many regulation-defying innovations

are undertaken with the explicit collusion of the regulatory authorities

who may be unable or unwilling to remove the regulations themselves.

Tax-Driven Innovations.

The tax authorities are usually much less willing to give in than the regulatory

authorities, so innovators must stay one step ahead of the game for the

innovation to survive. (Sometimes, however, the tax authorities will not

fight to close a loophole because they recognize that the loss of firms'

competitive position will mean minimal tax gathered relative to the cost

of more vigilant enforcement. Such was the case with the U.S. withholding

tax on corporate bonds issued in the United States and sold to non-residents.

American companies found that they could avoid the withholding tax by issuing

Eurobonds offshore and channelling the funds back home via Netherlands

Antilles subsidiaries, and the Internal Revenue Service did not close that

loophole for it was unlikely that foreigners would otherwise have bought

the domestic bonds and paid the 30% withholding tax.)

All Eurobonds are designed

to be free of withholding tax, and many have additional features that offer

tax advantages to issuers as well as investors. An example of the latter

is certain breeds of the perpetual floating rate note which give issuers

an approved form of capital, in effect preferred stock, but with the interest

(and in rare cases even the principal) being tax deductible.

Another technique that has

enjoyed many years of success is money market preferred stock, also called

auction rate preferred. Preferred stock pays a fixed dividend in lieu of

interest, and investors get preference over common shareholders, but the

dividend can be reduced or skipped if earnings are insufficient. Under

the tax laws of most countries interest is tax deductible while dividends

are not. But in some countries, notably the United States and Great Britain,

corporations owing shares in other corporations are only partially taxed

on dividends received. So if one U.S. company (A) issues preferred stock

to another company (B), B is taxed at a reduced rate on the dividends paid

on the preferred, but A cannot deduct the payments from taxes owed. So

companies with zero tax liabilities often issue preferred stock instead

of straight bonds.

A mutation of conventional

preferred stock is money market preferred stock, issued with short effective

maturities of (typically) seven weeks. The investor is told what the expected

dividend will be, but of course has no guarantee that it will be paid at

all given that he is buying shares. So the investment banker arranging

the deal holds an auction at the end of every seven weeks, replacing the

existing investors with new buyers. The new dividend to be paid is raised

or lowered in the auction process such that the money market preferred

is priced at par, at one hundred cents on the dollar. Typical language

in the prospectus might be: "At an initial dividend rate of 4.50% per

annum with future dividend rates to be determined by Auction every seven

weeks commencing on [date]." So the investor gets all his principal

and interest, just as though he had purchased commercial paper or some

other money market instrument. Although the rate paid is lower than comparable

money market instruments, the effective after-tax return is higher. For

the borrower who does not need the tax deduction that conventional interest

offers, this has proven to be a low-cost way of financing.

This announcement

appears as a matter of record only

NEW ISSUEFEBRUARY 1990

KREDIETBANK INTERNATIONAL

FINANCE N.V.

(Incorporated with limited

liability in the Netherlands Antilles)

¥3,000,000,000

13.5 per cent. Guaranteed

Nikkei Linked Notes

due 1991

unconditionally and irrevocably

guaranteed by

KREDIETBANK N.V.

(Incorporated with limited

liability in the Kingdom of Belgium)

Issue Price 101.125 per cent.

New Japan Securities Europe

LtdBankers Trust International Ltd

Daewoo Securities Co., Ltd.IBJ

International Ltd

Kredietbank N.V.Mitsui Trust

International Ltd

|

Back

to top

Constraints

Constraint-Driven

Innovations. Not all market imperfections stem from government regulations

and taxes; some are self-imposed, taking the form of trustee rules or standards

set by self-regulatory organizations. For example, many institutional investors

promise to invest only in instruments below a certain maturity or only

in "investment grade" bonds, meaning those rated BBB (or equivalent) and

above.

One common constraint is

the institutional investor's ability to buy and/or sell options, swaps

or other derivatives. When an important category of investor desires the

revenues that option writing provides, or the protection-plus-opportunity

that options buying offers, there is an opportunity for an investment banker

to devise a security that incorporates the sought-after strategy into a

specially tailored security. The embedded option or other derivative is

often then "stripped out" of the instrument by the same (or a collaborating)

bank. Such was the case with Nikkei-linked Eurobonds, which were issued

in droves in the 1980s and 1990s. Here's how they worked.

Case Study

Figure 3 reproduces the announcement

of a Nikkei-linked Eurobond issued by Kredietbank, one of Belgium's largest

commercial banks. Why would a bank whose principal business is in Europe

borrow three billion yen, and why linked to the performance of the Japanese

stock market as measured by the Nikkei index?

The answer is arbitrage.

Kredietbank,

together with its advisors Bankers Trust and New Japan Securities, is taking

advantage of a constraint on certain Japanese institutional investors,

namely their inability to sell options directly. Japanese institutional

investors have frequently sought higher coupons than are available in conventional

Japanese bonds, and have been willing to take certain risks to achieve

this goal. For many years one risk deemed acceptable by Japanese investors

was the risk that the Japanese stock market would plummet. The market had

achieved gain after gain and it looked like there was no turning back.

Some institutions were therefore willing to bet that the market would not

fall, say, more than 20% from its then current level. At the time the Kredietbank

deal was done, in 1990, the Nikkei index had soared to 38,000. Given these

conditions, a typical structure for a deal like this one was as follows.

First, as is sketched out

below, a Japanese securities firm like New Japan Securities identifies

investors, such as Japanese life insurance companies, who are interested

in a high coupon investment in exchange for taking an tolerable risk on

the Japanese stock market. The risk they are willing to take is equivalent

to a put option: they will invest in a note whose principal will be reduced

if, and only if, the Nikkei index declines below 30,400.

Kredietbank

|

[1]

¥13.5% Fixed

(6.3% above normal)

d

b

Implicit 1-year put option

on Nikkei index

[2]

|

Japanese

institutional investors

|

[3]

US$

Floating

L-d%

|

om

|

[3]

¥ Fixed

|

[4]

Kredietbank sells

o1-year

put option on Nikkei index

|

|

Bankers

Trust

|

[5]

BT sells 1-year put option

on Nikkei index

d

|

US

institutional investor with portfolio of Japanese stocks

|

Simultaneously, capital

markets specialists at the London subsidiary of Bankers Trust identify

a bank who is willing to consider a hybrid financing structure as long

as the exchange risk and equity risk are removed and the financing produces

unusually cheap financing. This bank is Kredietbank, whose goal is to achieve

sub-LIBOR funding. Bankers Trust will provide a swap that will hedge Kredietbank

against any movements of the yen or the Nikkei index. Specifically, Japanese

institutional investors such as life insurance companies will pay Kredietbank

¥3 billion for a 1 year note paying 13.5% annually ([1] in the diagram).

This is 6.3% better than the current 1 year yen rate of 7.2%. At maturity

the note will repay the face value in yen unless the Nikkei falls below

30,400, in which case the principal will be reduced according to a formula

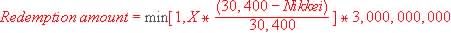

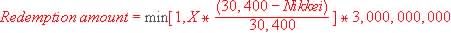

such as the following:

where

X is the number of options sold by the Japanese life insurance companies

to Kredietbank in exchange for the coupon subsidy [2]. The higher is X,

the greater the subsidy that can be paid.

where

X is the number of options sold by the Japanese life insurance companies

to Kredietbank in exchange for the coupon subsidy [2]. The higher is X,

the greater the subsidy that can be paid.

Kredietbank first changes

the yen received into dollars. It then enters into a yen-dollar currency

swap with Bankers Trust in which Kredietbank will pay (say) LIBOR-3/8%

semi-annually, and, at the end, the dollar equivalent of the initial yen

principal [3]. For example, if the spot rate is ¥135 per dollar, then

Kredietbank receives the sum of $22,222,222 (=¥3,000,000,000/(135¥/$))

at the outset, pays half of LIBOR-3/8% of this sum each six months, and

pays the same sum at the end.

In return Bankers Trust pays

Kredietbank the precise yen amounts needed to service the debt, namely

13.5% of ¥3,000,000,000 at the end of each year and the principal amount

as defined by the formula above, at maturity [4]. If the Nikkei happens

to fall below the "strike" level of 30,400 then Bankers Trust, not Kredietbank,

reaps the benefit.

Bankers Trust sells the potential

benefit to a third party, such as a U.S. money manager seeking insurance

against a major drop in the value of its portfolio of Japanese stocks [5].

The U.S. buyer of the Nikkei put pays Bankers a premium that exceeds the

"price" the Japanese investor received by a comfortable margin, leaving

enough to subsidize Kredietbank's cost of funds and leave something on

the table for the investment bankers.

Although Bankers Trust and

New Japan Securities might normally earn some fees from co-managing a ¥3

billion private placement such as this one, the real "juice" in the deal

comes from the pricing of the option, the put option on the Nikkei index,

that is embedded in the note. A key factor in making deals like this work

is adjusting the interest rate and the principal redemption formula so

as to leave everybody satisfied.

Back to

top

Segmentation-Driven Innovation.

Academics have long debated whether securities tailored to particular investment

groups can actually save issuers money, or whether supposed advantages

are eventually arbitraged out. The huge volume of CMOs4

in the United States seem to favor those who argue that splitting up cash

flows to meets particular groups of investors' needs and views does provide

value added. These instruments, some of which take the form of Eurobonds,

divide the cash flows from mortgage pools into tranches based on timing

of principal redemption (for investors with different maturity needs) and,

in some cases, segregate the interest from the principal.

Distinct market segments

of several kinds seem to exist in the international financial markets.

Many investors, of course, have a strong currency preference. Credit risk

problems prevent the majority of these from doing swaps and forwards themselves

to arbitrage out differences. Some view a currency as risky in the short

term but stable in the long term; it is for these that the dual currency

bond was invented. The example that follows shows how these work.

Example

Dual currency bonds pay interest

in one currency and principal in another. The interest rate that they pay

lies somewhere between the prevailing rates in the two currencies.

For example the Sperry Corporation,

through a Delaware financing subsidiary, issued a US$56 million dual currency

bond in February, 1985. The interest rate, payable annually in dollars,

was 6 3/4%. The principal, however, was equal to 100 million Swiss francs.

The final maturity was February, 1995.

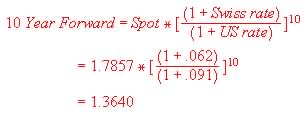

The spot exchange rate at

the time was SF1.7857 per US dollar, making SF100 million equivalent to

$56 million. The 10 year US dollar and Swiss franc interest rates at the

time were 9.1% and 6.2 %, respectively, for comparable single currency

bonds.

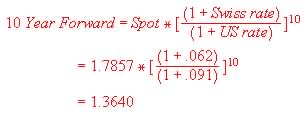

How was the interest rate

on the Sperry bond set? One can estimate the "correct" rate as follows.

Recognizing that Sperry probably hedged the principal to be repaid in 10

years, we need the Swiss franc/ US dollar 10-year forward exchange rate

to see what the repayment really cost Sperry. From interest rate parity,

the forward rate can be calculated as follows:

From this, Sperry's dollar

repayment amount is SF100,000,000/1.3640=$73,315,169. So Sperry repays

$17,315,169 more than it borrowed. Expressed as an annual annuity, this

is $1.134,258. This is 2.03% of $56 million, so the theoretical rate should

be 7.07%

|

Back

to top

Asset-Backed

Securities in Turkey

The Turkish Capital Markets

Board has aggressively sought to modernize the country's capital market,

and in 1992 it pushed though a decree that enabled Turkish banks to securitize

certain assets.

The first such deal was done

by a privately-owned bank, Interbank, which issued TL4.25 billion in securities

backed by its leasing receivables. The issue had maturities of one to 10

months and bore an interest rate of 72.36 percent. At the time, one year

bank deposits paid about 70 percent and three month deposits about 62 percent.

Other institutions, such as Pamukbank and Yapi ve Kredi, followed with

issues backed by consumer credits, mortgages, export receivables and other

assets.

In these deals and ones like

them, the assets are sold to a special purpose company which finances the

purchase with a cushion of equity (provided by the sponsor) and a public

debt issue or issues. Conditions for them to work include protection of

the issuer from additional taxes, accounting and regulatory treatment that

allows the sponsor to take the assets off its balance sheet, and protection

for the investor including proper isolation of the assets' cash flows from

the condition of the sponsor. The debt being issued typically has sufficient

"overcollateralization" by the assets to achieve an investment grade rating.(9.10%-2.03%).

The difference between the actual rate paid and the theoretical rate is

Sperry's savings, assuming our calculations are correct. In point of fact

the forward rate is unlikely to conform precisely to interest parity and

there are additional costs to a deal like this so Sperry's savings would

be smaller.

Nevertheless it is clear

that in this deal as in many of this kind the investor is receiving less

than the theoretical rate. Why? For the issuer to tailor a bond to investors'

needs and views, there must be some cost savings. And the investor cannot

replicate such structures directly, for small investors would never be

able to enter into a 10 year forward contract.

Securitization of mortgages,

car loans, credit card receivables and other assets with predictable cash

flows represents a whole category of segmentation-driven innovation that

is becoming more prevalent outside the United States--in Britain, for example,

and in the Euromarket, and even in developing countries such as Mexico.

The box describes the use of the technique in Turkey.

Back to

top

Understanding

New Instruments: The Building Block Approach

In this section and the next

we offer two related approach to the analysis of hybrid instruments such

as the ones discussed above.

A number of attempts have

been made to categorize new financial instruments.

Some class them by interest rate characteristics--fixed, floating or

floating capped, for example. Others seek to divide them by rating,

or maturity, or equity-linkage, or tax status. The Bank for International

Settlements in a classic study categorized innovations according to their

role: risk transferring, liquidity-enhancing, credit-generating and equity-generating.

The best way to group

instruments depends in large part on the purpose for which the grouping

is being made. The building block approach is used to learn how to construct

or reverse engineer existing or new instruments. The idea is not so much

that the reader will necessarily learn much new about instruments that

exist now, but rather to develop a method that can be applied to new instruments

as they appear.

The premise of the building

block approach is that hybrid instruments can be dissected into simpler

instruments that are easier to understand and to price. Many, although

by no means all, hybrid securities can be broken down into components consisting

of:

• Bonds (creditor

(long) or debtor (short) positions in zero coupon bonds)

• Forward contracts

(long or short forward positions in a currency, bond, equity or commodity)

• Options (long or

short positions in calls or puts on a currency, bond, equity or commodity)

The building block approach

is to combine two or more bonds, forwards or options to create the same

cash

flows as some more complex instrument. A simple example: a coupon-paying

bond is simply a series of zero-coupon bonds equal to the interest and

a larger zero at the end equal to the principal. Arbitrage should ensure

that the price of the coupon bond equals the sum of the prices of all the

little zeroes. Another example: a zero coupon bond in one currency, plus

a forward contract to exchange that currency for another, is the same as

a zero coupon bond in the second currency.

We have already encountered

a number of applications of the building block approach without calling

it that. Chapter 7 showed how a futures contract can be broken into a series

of repriced forward contracts. In Chapter 13 we learned that a currency

swap is equivalent to a fixed rate bond in one currency and a short position

in a floating rate note in another currency. And in Chapter 15 we constructed

commodity price linked instruments from conventional bonds and forward

contracts on commodities.

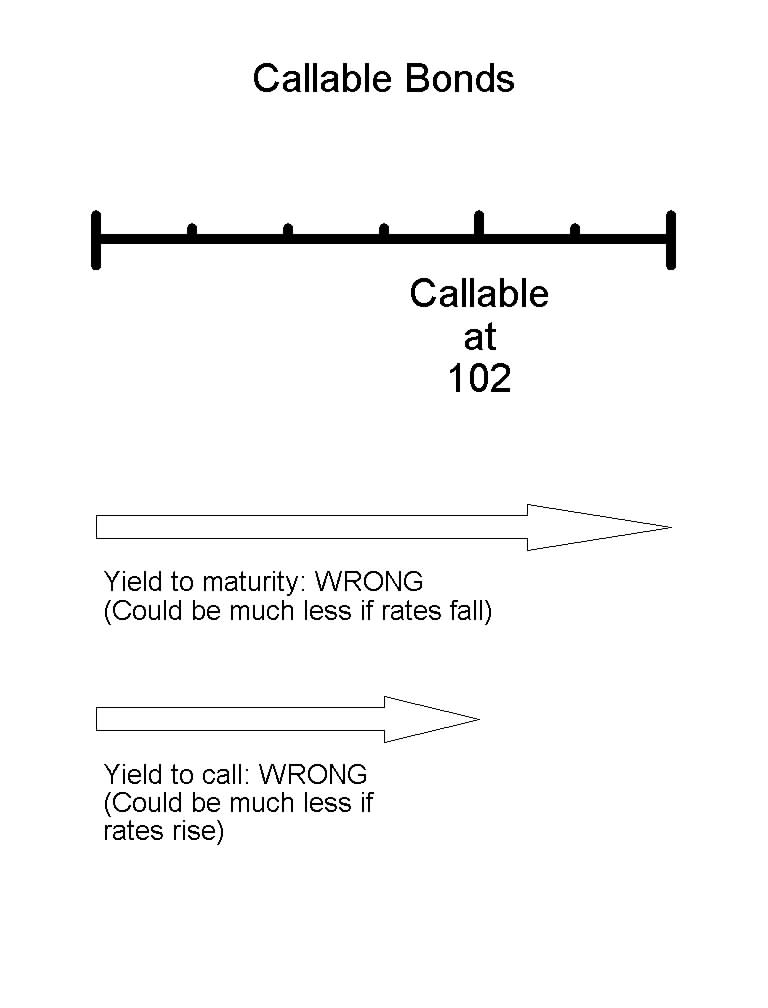

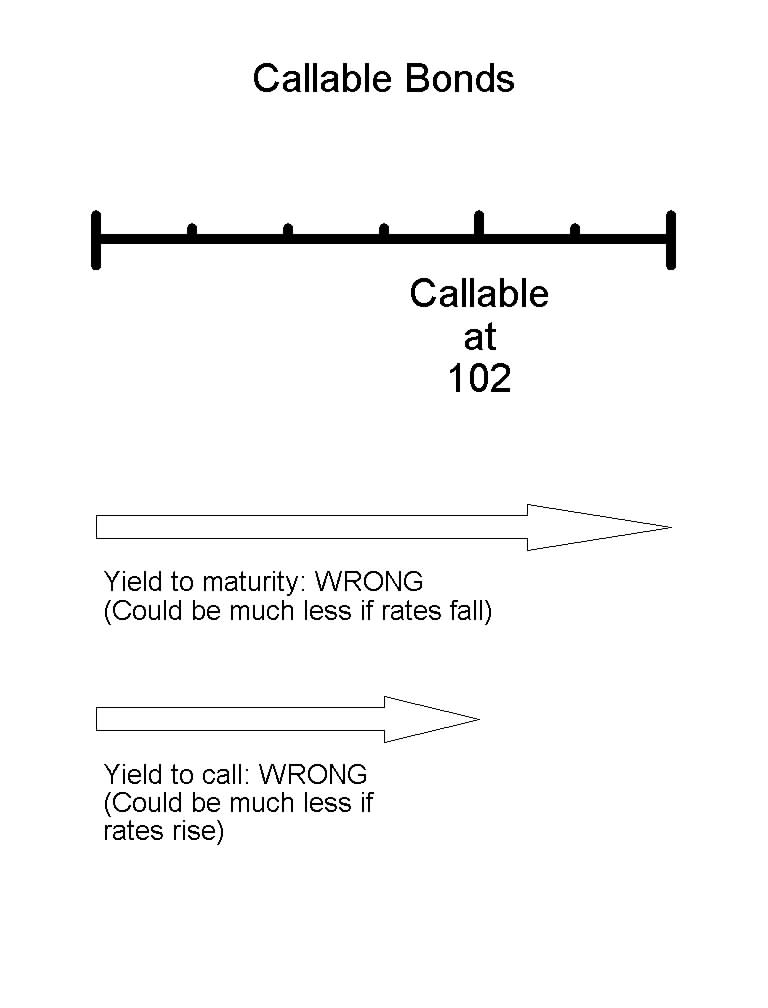

Let us illustrate how the

building block method lets one better judge the value and pricing of a

hybrid instrument than more ad hoc approaches by decomposing a callable

bond into its components. Discussions by brokers with their investor clients

often focus on the yield to maturity versus the yield to call

of a callable bond. They like to point out when a callable bond appears

superior to a non-callable bond when judged by either criterion. As Figure

4 illustrates, however, the investor cannot judge a callable bond by either

or even both measures of return. Whichever way rates move, the investor

gets the worst of both worlds, and should be compensated fairly for this

risk. The way to judge the fairness of the bond's pricing is not by looking

at yield but rather at the value of the components, and then comparing

them with the investor's practical alternatives given his or her needs,

constraints and views.

Let us illustrate how the

building block method lets one better judge the value and pricing of a

hybrid instrument than more ad hoc approaches by decomposing a callable

bond into its components. Discussions by brokers with their investor clients

often focus on the yield to maturity versus the yield to call

of a callable bond. They like to point out when a callable bond appears

superior to a non-callable bond when judged by either criterion. As Figure

4 illustrates, however, the investor cannot judge a callable bond by either

or even both measures of return. Whichever way rates move, the investor

gets the worst of both worlds, and should be compensated fairly for this

risk. The way to judge the fairness of the bond's pricing is not by looking

at yield but rather at the value of the components, and then comparing

them with the investor's practical alternatives given his or her needs,

constraints and views.

So to better evaluate

and compare different callable (and non-callable) bonds, decompose the

bond into

(1) Noncallable

bond (bought by the investor)

and

(2) Call option (sold

to the issuer by the investor)

Find the value of each component,

to discover whether the composite bond is overpriced or underpriced relative

to the investor's realistic alternatives. One method for doing so is as

follows:

1. Use the market

yield on similar noncallable bonds to find the value of the straight bond.

2. Subtract the price

of the callable bond from the value of the non-callable bond to find the

price received for the call option.

3. Compare that with the

value the investor could have received from selling call options in the

market (may use option pricing model), or compare it with the implicit

value of call options embedded in other callable bonds from comparable

issuers currently available in the market.

Another practical application

of the building block method is in the decomposition of so-called inverse

floating rate notes, also known as reverse floaters or yield curve notes.5

These instruments have been issued in large numbers in the United States,

Germany and elsewhere during the past decade.

Example

In February 1986 Citicorp

issued a $100,000,000, five-year Eurobond which it termed "adjustable rate

notes." The deal had the following features, as described in the preamble

to the prospectus:

Interest on the Notes

is payable semiannually on February 27 and August 27 beginning August 27,

1986. The interest rate on the Notes for the initial semiannual interest

period ending August 27, 1986 will be 9.25% per annum. The Notes will mature

on February 27, 1991 and will not be subject to redemption by Citicorp

prior to maturity.

So far so good. It's a 5-year

non-callable note with a generous first coupon (6 month rates at the time

were in the region of 8c%).

The preamble went on to say that

The interest rate for

each semiannual interest period thereafter, determined in advance of the

interest period as set forth herein, will be the excess, if any, of (a)

17d%

over (b) the arithmetic mean of the per annum London interbank offered

rates for United States dollar deposits for six months prevailing on the

second business day prior to the commencement of such interest period.

This is a lawyer's way of

saying that the notes pay 17d%-LIBOR,

but never less than zero.

Let's reverse engineer this.

Seeing an instrument paying the difference between two rates reminds one

of a swap. Indeed part of this instrument is like an interest rate swap

and part is a bond (after all the investor is lending money). To replicate

the cash flows of the Citicorp note,

(1) Buy a 5-year

fixed rate bond paying 8.6875% (17.375/2), and

(2) Enter into a 5-year swap

where you receive fixed 8.6875% and pay LIBOR.

You'll now receive 17.375%

minus LIBOR every 6 months. But one more thing: you'll never have a negative

payment under the Citicorp deal, so to mimic it you should also

(3) Buy a an interest

rate cap at 17.375%. This pays the difference between LIBOR and 17.375%

should LIBOR exceed that level. It's deep out of the money so it's cheap.

These three transactions

precisely

replicate the cash flows of the Citicorp inverse floating rate note.

Now you are in a position to evaluate the Citicorp note against other investments.

If the five-year bond yield (and by implication the swap rate) exceeds

8.6875% (as it did in February 1986) by a sufficient amount, it may be

worthwhile replicating the instrument rather than buying it. For example,

if the bond and swap rates were 9%, transactions (1) and (2) would reap

18% instead of 17.375%. In reality most individuals and money market investors

who might purchase a reverse floater do not have access to the swap market

and/or may not be permitted to hold fixed-rate bonds, so this deal may

look better even if its pricing is such as to give Citicorp cheap financing.

Even so, the autopsy can serve a purpose: one realizes that the effective

duration of this instrument is that of two five year bonds, minus a six

month instrument, unlike other floating rate notes (which typically have

a duration of .5 or less). So it has a high degree of price risk.

|

The last point in the example

above--the price risk factor--may be more important than knowing how to

duplicate the instrument. Moreover many new financial instruments, such

as those with prepayment options that are contingent on corporate events

rather than on interest rate conditions--are not easily broken down. For

these one may need complex option-based models. Both considerations suggest

that sometimes a price-based analytic approach may be more useful.

Back to

top

Hedging

and Managing New Instruments: The Functional Method

This section describes a

second approach, which we may term the functional method, to the

analysis of hybrid or complex securities. Its aim is not dissection, for

one cannot always break instruments down for practical purposes, but rather

to describe the price behavior of any hybrid bond or other instrument.

The method helps to show which instrument serves precisely what purpose

for particular investors or issuers. The method can also be used to create

optimal hedges or arbitrages for one instrument against another.

The premise of the functional

approach is that for practical purposes the only thing that matters about

an international bond or other instrument is changes in its value--in its

market price, if it is tradeable. Although one does not always think of

a bond this way, in the final analysis one seldom cares more about a bond's

beauty or soul than about its market value.

The key idea of the functional

approach is that the value of every financial instrument can be characterized

as a function of a set of economic variables. These variables might

be ones such as the three-month US Treasury bill rate or the dollar-sterling

spot exchange rate, or the Financial Times sub-index of consumer electronics

stocks or the price of an individual company's stock. The presumption is

that each instrument's payouts are contractually linked to the values or

outcomes of a set of variables or events. If it is true that we can in

principle express the value of every financial instrument as a function

of a set of known variables like those listed above, then it seems that

in order to understand what an instrument does, and what it's good for,

and how its price behaves under different scenarios, we have to know three

things:

• The precise

variables or factors that have the most effect on the instrument's

price, and

• The functional relationship

that shows how a given movement in each variable's value translates into

changes in the instrument's value, and

• The relationship between

the factors--whether, in particular, specific factors are positively,

negatively or nor at all correlated with each of the other significant

factors.

Example

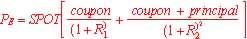

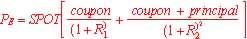

Consider an example: a two-year

Euroyen bond. Our task is to describe, as fully as possible, its price

behavior in US dollars. We will attempt to do so in three stages.

1. Identify the variables

• Yen-dollar exchange

rate, since we are interested in the dollar price of the bond.

• 2-year Japanese interest

rate on an equivalent bond.

• 1-year Japanese interest

rate (since coupons are paid annually in the Euroyen market, the bond's

value will be affected by the present value of the first year's coupon).

2. Describe the functional

relationship between the bond's price and the set of key variables.

Here's where the building block approach can be helpful: the valuation

of the components of the security may yield the valuation of the hybrid

instrument as a whole. In the case of the US dollar value we can say it

is the present value of the cash flows in yen, all translated into dollars

at today's spot exchange rate:

where P is the

price of the bond, SPOT the dollar/yen spot exchange rate and R

the US interest rate used to discount cash flows.

3. Estimate the correlation

among the variables. We cannot fully understand the influence of any

one variable on the bond unless we know whether that variable is independent

of the others. Japanese interest rates of different maturities are highly

correlated, and probably inversely related to the yen-dollar spot exchange

rate (yen per dollar). In real life we have to make approximations. For

most purposes it would probably suffice to ignore the interest rate-exchange

rate relationship (a poorly understood one at best), and assume that the

1-year and 2-year Japanese interest rates move perfectly in tandem.

This allows us to simplify

the relationship and to use the duration concept to show the sensitivity

of Euroyen bond prices to 2-year Japanese interest rates. We then simply

translate the price change into the US dollar value at the spot exchange

rate, giving the dollar price change in the Euroyen bond.

|

Back to top

Application:

Valuation of an Oil-Linked Bond

The functional method requires

a model for valuation of the instrument. This is not always easy to devise

with precision. In this section we describe an effort to value a bond with

embedded long term options on the price of oil. The oil-linked bond was

issued by Standard Oil of Ohio Company at the end of June 1986. The bond

represented $37,500,000 face value of zero coupon notes maturing on March

15, 1992. The holder of each $1000 note was promised par at maturity plus

an amount equal to the excess, if any, of the crude oil price (West Texas

Intermediate) over $25, multiplied by 200 barrels. The limit for the WTI

price was $40, so that the maximum the investor could receive at maturity

was ($40-$25)x200=$3000, plus the par value of $1000. In addition, each

holder could redeem his or her note before maturity on the above terms

on the first and fifteenth of each month beginning April 1, 1991.

For the purposes of calculating

the settlement amount, the oil price was defined as the average of the

closing prices of the New York Mercantile Exchange light sweet crude oil

futures contract for the closest traded month during a "trading period"

defined as one month ending 22 days before the relevant redemption or maturity

date.

Let us decompose the Standard

Oil issue. Each note can be regarded as a portfolio consisting of :

(a) a zero-coupon

corporate bond, plus

(b) one quasi-American"

call option with an exercise price of $25, plus

(c) a short position in

one quasi-American call option with a $40 exercise price.

The "quasi-American" feature

results from the intermittent early exercise right in the last year of

the bond's life.

Making some simplifying assumptions,

Gibson and Schwartz have been able to develop a valuation model for this

bond and to test it using actual trading prices for the issue. The model

was based on arbitrage-free option pricing principles; the data were actual

(but infrequent) transaction prices of the bond over the period August

1, 1986 to October 14, 1988. Transaction prices were used in preference

to bid and ask quotations since the spread was too wide, averaging 10%

of the bid price. Gibson and Schwartz found that the key variables in the

valuation of oil and similar commodity linked bonds were the volatility

and the convenience yield.

On its own, the function

or formula helps price the instrument and can be used for sensitivity analysis

in, say, portfolio management. But its chief value is in combination with

similar analysis applied to other instruments. As long as there is some

overlap in the functional variables, we can perform comparative analysis

to show the price behavior of a combination of instruments--for

hedging or arbitrage purposes, or to identify the most effective way of

positioning in a particular market. The box gives an example.

Back to

top

Hybrids

in Corporate Financing:

Creating a Hybrid Instrument

in a Medium Term Note Program

Hybrid instruments, we have

seen, are widely used by corporations and banks in financing. Among the

most versatile of instruments for the design and issuance of hybrid claims

is the medium term note, for the distribution technique of MTNs lends itself

to being tailored to one or a few specific investors. This section will

describe the design and use of a hybrid instrument that was used by a major

European bank as part of its funding. The names have been disguised but

the sequence of events and the technique itself are close to the original.

The

story begins in Munich, where Bavaria Bank has its headquarters. To help

meet its ongoing funding requirements the bank recently set up a medium

term note program of the kind described in Chapter 10. The program was

managed by EuroCredit, an investment bank in London.

EuroCredit,

the intermediary, is a well established and experienced bank in

the Euromarkets. Its staff has the technical and legal background needed

to arrange structured financing, and has trading and positioning capabilities

in swaps and options--a "warehouse". Its underwriting and placement capabilities

lie not so much in the capital it has to invest in a deal, but rather in

its relationships with investors and with corporations, banks and government

agencies that use over the counter derivatives. Indeed with recent economic

conditions portending a rise in interest rates, EuroCredit has perceived

mounting interest in caps, swaptions and other forms of interest rate protection.

EuroCredit has a high credit rating, making it an acceptable counterparty

for long term derivative transactions. These capabilities make it suited

to the creation of hybrid structures for financing.

An

official of EuroCredit described the background to the deal :

"The

issuer,

Bavaria has excellent access to the short term interbank market, but was

seeking to extend the maturity of its financing. It was looking for large

amounts of floating-rate US dollar and German mark funding for its floating-rate

loan portfolio.

It

had set a target for its cost of funds of CP less 10, in other words the

Eurocommercial paper rate minus .10%. Because its funding needs were ongoing

and any new borrowing would replace short term interbank funding, it was

not overly concerned with the specific timing of issues, or the amount

or maturity. This flexibility made a medium term note program the ideal

framework for funding. Best of all, Bavaria was willing to consider complex,

hybrid structures as long as the bank was fully hedged.

"We

have a standard sequence of steps that we follow for borrowers of this

kind [see box]. What we now needed was to identify an investor or investors

for whom we could tailor a Bavaria note.

"An

institutional investor client of ours, Scottish Life, has a distinct

preference for high grade investments, so Bavaria's triple-A rating brought

them to mind. They have been on the lookout for investments that would

improve their portfolio returns relative to various indexes and to their

competition. An initial discussion with them revealed that they invest

in both floating rate and fixed rate sterling and US dollar securities.

Like other U.K. life insurance companies, they are constrained in certain

ways; in particular, they can buy futures and options to hedge their portfolio

but they cannot sell options."

The

stage was now set for EuroCredit to arrange a note within its medium term

note program, one designed to meet Scottish Life's needs and constraints,

and to negotiate the terms and conditions with the various parties.

The

deal that emerged was a US dollar hybrid floating/fixed rate note paying

an above-market yield in which Bavaria had the right to extend the maturity

from 3 years to 8 years. "Although it was a really private placement,"

said

the EuroCredit official, "we wrote it in the form of a Eurobond with

a listing in Luxembourg. This was to meet Scottish Life's requirement that

it only buy listed securities."

The following "term sheet"

summarizes the main features of the note.

ISSUER:

|

Bavaria Bank AG

|

AMOUNT:

|

US$ 40 MILLION

|

COUPON:

|

First 3 years:

semi-annual LIBOR + 3/8% p.a., paid semi-annually

Last 5 years: 8.35%

|

PRICE:

|

100

|

MATURITY:

|

February 10, 2000

|

CALL:

|

Issuer may redeem

the notes in full at par on February 10, 1995

|

FEES:

|

30 bp

|

ARRANGER:

|

EuroCredit Limited

|

The crucial elements are

the coupon and call clauses. First, to appeal to the

investor, the issuer has agreed to pay an above-market rate on both

the floating rate note and the fixed rate bond segments of the issue

FRN portion:

.75% above normal cost

Fixed portion:

.50%

above normal cost

But by having the right

either to extend the issue or terminate it after three years, the issuer

has in effect purchased the right to pay a fixed rate of 8.35% on

a five-year bond to be issued in three years time. Through its investment

bank, the issuer will sell this right for more than it cost him, and so

lower his funding cost below normal levels. This is illustrated in

the following diagram.

BAVARIA

BANK

|

Bavaria

sells 3 year floating

rate note paying LIBOR-d%

d

For an additional ¾%

pa, Bavaria buys right to sell 5 year fixed rate 8.35% note to SL

in 3 years

b

|

SCOTTISH

LIFE

|

o

|

For 1% pa, Bavaria

sells

EuroCredit a swaption (the right to pay fixed 8.35% for 5 years

in 3 years)

|

|

|

EUROCREDIT

|

EuroCredit sells

the swaption to a corporate client seeking to hedge its funding costs against

a rate rise

|

|

One could argue that Scottish

Life would have been better off selling the swaption directly to EuroCredit

or even to EuroCredit's client. This is not realistic: the institutional

investor is not permitted to write options directly, although as is typical

it is permitted to buy callable bonds and other securities with options

embedded. Moreover it may not have a sufficient credit rating to enable

it to sell stand-alone long term derivatives at a competitive price.

These constraints are necessary

but not sufficient conditions for a hybrid bond such as the one described

to become reality. The characteristics of the intermediary are often underestimated.

Not only must it have the "rocket scientists" who can devise and price

complex options, but it must also be able to trade and position them so

as to be able to offer a deal quickly rather than having to wait around

for a buyer of the derivative before the deal can be consummated. It must

have excellent institutional investor relationships preferably in places

"where the money is" like the United States, Germany and Japan. Insight

into institutional and corporate needs and constraints is a scarcer commodity

than a Ph.D. in physics from Moscow State University. The financial institution

must have experience and credit and people that can be trusted. Few banks

qualify.

Back to

top

Structured

Financing

Structured

Financing: A Sequence of Steps

The following sequence

of seven steps gives an indication of how investment banks arrange specially-structured

financing, often tailored to investors' requirements, in the framework

of a medium term note program.

1. Initiate medium

term note program for the borrower, allowing for a variety of currencies,

maturities and special features

2. Structure a MTN

in such a way as to meet the investor's needs and contraints

3. Line up all potential

counterparties and negotiate numbers acceptable to all sides

4. Upon issuer's and

investor's approval, place the securities

5. For the issuer,

swap and strip the issue into the form of funding that he requires

6. Sell the stripped-off

derivative to a corporate or investor client that requires a hedge

7. Offer a degree of

liquidity to the issuer by standing willing to buy back the securities

at a later date.

|

Back to top

Global

Financial Markets in the Next Decade

Nobody knows for sure what

the future holds. Even so, the practitioner and observer of global financial

markets can be confident that innovation and adaptation of instruments

will continue. This and some of the conclusions reached in earlier chapters

allow us to venture a few predictions.

First, the structure of

individual economies, and of the world economy, is in a state of change.

As a result there is a great challenge for creativity in international

financial techniques to with the problems of, among others, (1) the changing

demographic composition of the industrial countries, (2) the emerging capital

markets, (3) developing economies that lack adequate domestic financial

markets and banking systems, and (4) the once-socialist economies

in transition.

Second, as new countries

compete more vigorously with the old, the existing order will break down.

This

means that any financial institution resting on its laurels will come under

great competitive threat, and to survive and thrive must change in response

to the new order--whatever it is.

Third, global and regional

monetary arrangements such as the European monetary system will continue

to be in flux for some years to come. Few believe that unfettered freely-floating

exchange rates will eliminate adjustment problems. Multi-year deviations

from purchasing power parity will persist. Yet countries seeking the discipline

of fixed exchange rate arrangements will have to contend with the strains

in money and currency markets that accompany an attempt to fix exchange

rates before economic policies are unified.

Fourth, in the light of these

economic changes and pressures, investors, banks and broker-dealers

must

vastly upgrade their understanding of, and ability to manage, complex

financial instruments, particularly option-based instruments such as

those described in this and preceding chapters.

Fifth, with the erosion of

barriers to international competition in goods, services and financial

markets, there is an increasingly strong inter-relationship among money,

bond, currency, commodity and equity markets, and between the derivative

markets in each of these categories.

Sixth, despite the preceding

statement, academic and practical understanding of exchange rate determination,

and of the determination of equity prices in an international context,

is still in a state of flux. For some years to come the jury will be

out on some of the theories propounded in this book, as well as on the

ones that inevitably replace them.

Finally, policy-makers

will face severe demands at the micro as well as at the macro level.

Bank and securities market regulators have a long road to tread in developing

credible standards for credit risk and market risk control, as well as

for disclosure requirements. On the other hand with banks losing their

privileged positions, any increase in regulatory costs inserts a wedge

between investors and borrowers, driving companies and individuals to foreign

or offshore markets.

In short, neither regulators

nor practicing bankers nor academic scholars can afford to be complacent

about the global financial markets in the decade to come.

Back to

top

Summary

and Conclusion

Financial innovations are

challenging and fun. Most of the time they do not work. When they do, it

is because they successfully overcome some market imperfection. This chapter

has sought to help the reader understand the conditions that are necessary

for hybrid securities to succeed as well as to learn their use as investment

and financing vehicles.

Imperfections that drive

innovations include transactions costs and the costs of monitoring performance,

government regulations, taxes, constraints and market segmentation.

Most instruments of the international

capital market can be broken down into simpler securities. These elementary

securities or building blocks include zero-coupon bonds, pure equity,

spot and forward contracts and options. Reverse financial engineering can

be done to figure out how a hybrid instrument could be replicated using

simpler instruments.

For many purposes what we

want to know is how the instrument will behave given changes in

the certain market variables. The functional method regards every

such instrument or contract as bearing a price or value, which in turn

bears a unique relationship to some set of variables such as interest rates

or currency values. This can be complex, but the idea is simple and can

be illustrated in the matrix below. To fill in the blank cells for a particular

security, ask whether the instrument's value bears a forward-type (linear)

or and option-type (kinked) relationship to the market variable, and what

that relationship is.

A HYBRID BOND MATRIX

|

FORWARD-TYPE

LINKAGE

|

OPTION-TYPE LINKAGE

|

INTEREST RATE

|

|

|

CURRENCY

|

|

|

COMMODITY

|

|

|

EQUITY INDEX

|

|

|

EQUITY OF COMPANY

|

|

|

As numerous examples in

the chapter demonstrated, an analytical approach, even one that make simplifications

for practical reasons, can be of great value to investors and issuers who

wish to better understand the risks of instruments offered to them by banks.

The approach can also be used to identify arbitrage opportunities between

instruments, and to hedge one instrument with another.

Dissecting new financial

instruments offers great challenges, and encourages a way of thinking that

may help equip us to adapt to the significant changes in the world economy

that are inevitable in the next decade.

Selected References

G. Dufey and Ian H. Giddy,

"Innovation in the International Financial Markets" (with G. Dufey), Journal

of International Business Studies (Fall 1981), 33-52.

Joseph D. Finnerty, "Financial

Engineering in Corporate Finance: An Overview," Financial Management,

Vol. 17, No. 4 (Winter 1988), 14-33.

Clifford W. Smith, Charles

Smithson and D Sykes Wilford, Managing Financial Risk (Ballinger,

1990).

Julian Walmsley, The New

Financial Instruments (John Wiley & Sons, 1988)

Risk Magazine, various

issues.

Journal of Financial Engineering,

various issues.

Back to

top

Conceptual

Questions

1. In choosing an investment